On February

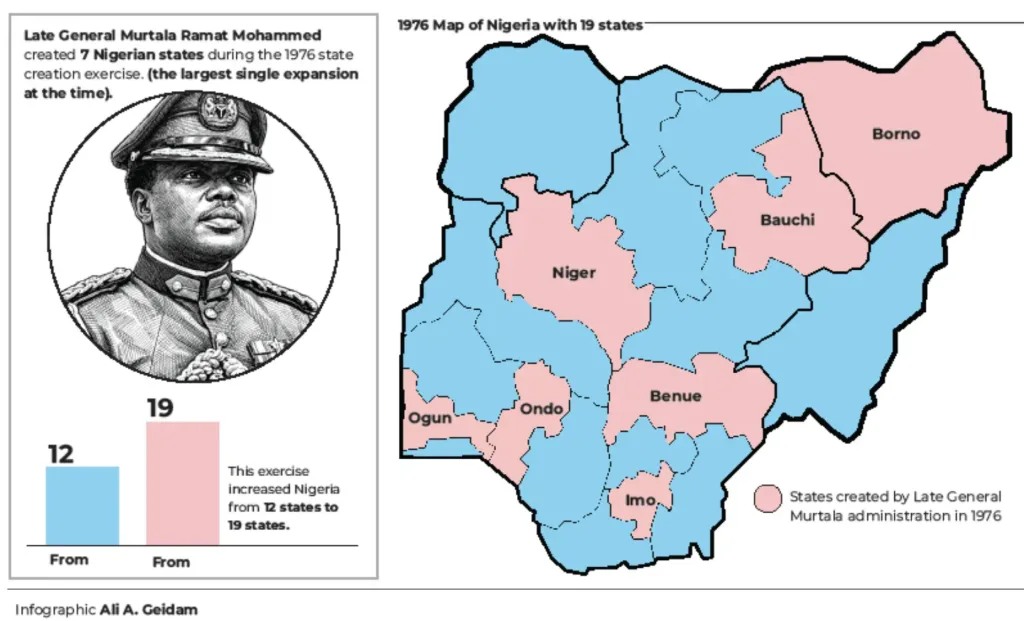

3, 1976, just ten days before his assassination, Nigeria witnessed one of the most consequential moments in its administrative history. The military government of General Murtala Ramat Mohammed announced the creation of seven new states, expanding the federation from 12 to 19 and fundamentally reshaping the country’s political and territorial architecture.

The decision, delivered through nationwide radio broadcasts, was bold, far-reaching and unmistakably reflective of Murtala Mohammed’s governing style.

He was known as a decisive person, reform-driven and impatient with inertia. Coming barely six months into office, and days before his life was cut short, the exercise would become one of the most enduring legacies of his brief but impactful rule.

The seven states created on that day were Bauchi, Benue, Borno, Imo, Niger, Ogun and Ondo. Historians believe that together, the seven states represented an attempt to address long-standing agitations for closer governance, reduce the overbearing power of the old regions and foster a more balanced federation through administrative decentralisation.

General Murtala Mohammed was explicit about his reasoning. In announcing the state-creation exercise, he argued that Nigeria’s size, diversity and history made excessive centralisation both inefficient and dangerous. Large regions, he believed, had become too distant from the people they governed, breeding alienation, uneven development and political tension.

State creation, in his view, was not merely an administrative adjustment but a nation-building tool. By bringing government closer to the people, the new states were expected to promote equitable development, deepen national unity and reduce ethnic and regional domination within the federation. He maintained that Nigeria’s unity would be better sustained not by force or rhetoric, but by fairness, inclusion and administrative balance.

This same philosophy informed another landmark decision taken almost simultaneously, which is the relocation of Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory from Lagos to Abuja.

Murtala argued that Lagos, beyond being congested and overstretched, had become symbolically and geographically unsuitable as a national capital. Its coastal location, ethnic dominance and severe infrastructural strain made it, in his words, “unsatisfactory as the seat of the Federal Government.” Abuja, by contrast, was centrally located, sparsely populated, and free from the ethnic and religious claims associated with older cities. It was conceived as a neutral capital that would belong equally to all Nigerians.

Together, the creation of new states and the decision to build Abuja reflected a coherent vision and a more balanced, decentralised and inclusive Nigerian federation.

What makes the February 3, 1976, exercise particularly historic is its timing. It was announced just ten days before General Murtala Mohammed was assassinated on February 13, 1976, during an abortive coup in Lagos. At the time, he was only 37 years old and had been in office for just over six months.

The seven states thus stand today as tangible reminders of a leadership era defined less by longevity than by intensity and impact.

Following Murtala Mohammed’s assassination, there were fears that many of his initiatives might be reversed or abandoned. However, his successor, General Olusegun Obasanjo, a key member of the same administration, opted for continuity. He retained the seven states, proceeded with the Abuja project and carried through the transition programme that culminated in the return to civilian rule in 1979.

This continuity ensured that the February 3, 1976, decisions were institutionalised rather than treated as the unfinished ideas of a fallen leader.

How the 7 states emerged

Findings revealed that each of the seven states created in 1976 emerged from specific historical and administrative contexts.

Bauchi and Borno states, for instance, were carved out of the defunct North-Eastern State, ending decades of administrative over-centralisation in a vast and diverse region. The split allowed for more focused governance and improved administrative reach across a geographically expansive area.

Benue State emerged from Benue-Plateau State, giving greater political identity and administrative autonomy to the Tiv-dominated areas and responding to long-standing demands for self-representation.

Niger State was created from the former North-Western State, bringing governance closer to communities spread across one of the largest territories in the country.

Ogun and Ondo states were carved out of the old Western State, a region historically associated with intense agitations for state creation, driven by concerns over internal balance, development priorities and political representation.

Imo State emerged from the East Central State, addressing minority concerns within the former Eastern Region and laying the groundwork for future administrative restructuring in the South-East.

Exactly fifty years on, the seven states have expanded significantly in population, infrastructure and political relevance. Some of them have also been further subdivided in subsequent state-creation exercises, underscoring the continuing relevance of Murtala’s decentralisation logic.

Gombe State was carved out of Bauchi in 1996; Yobe State emerged from Borno in 1991; Abia State was created from part of old Imo in 1991; Ekiti State was carved out of Ondo in 1996 while Benue, Niger and Ogun have remained territorially intact since 1976.

Similarly, over the past five decades, the seven states have produced leaders at the highest levels of national life, including governors, ministers, military chiefs, legislators and, in some cases, vice-presidential and presidential figures. They have contributed significantly to Nigeria’s economy through agriculture, industry, energy, commerce and human capital development.

Ogun has emerged as a major industrial hub; Benue has sustained its reputation as a food-producing state; Niger hosts critical hydroelectric infrastructure; Borno and Bauchi play key roles in agriculture and trade; Imo has remained a centre of education and entrepreneurship; while Ondo has contributed through agriculture, solid minerals and human resources.

But despite the milestones recorded in the affected state, observers believe that their 50th anniversary also invites sober reflection, considering that many of the promises that accompanied state creation anchored on improved governance, accelerated development, enhanced security and economic self-reliance remain only partially fulfilled.

Bauchi continues to grapple with high poverty levels, low internally generated revenue and youth unemployment.

Sadly, Bauchi and Gombe states have issues over the ownership of the Kolmani Oil and Gas field as the two have, in the past few years, continued to lay claims to the oil wells.

The site, with Oil Prospecting Licences 809 and 810, cutting across Kolmani One, Two, Three, Four and Five, was commissioned by late President Muhammadu Buhari, and it reportedly contains one billion barrels of crude oil reserves and 500 billion standard cubic feet of gas.

Benue’s development has been undermined by persistent farmer-herder conflicts, displacement of rural communities and weak agro-processing capacity, despite its agricultural potential.

Ironically, it was just yesterday that a Federal High Court in Abuja directed the remand of some suspects allegedly behind the violent attacks in Yelwata Community in Benue State, in which about 150 persons died, and property was destroyed.

Borno remains burdened by the long-term effects of insurgency, humanitarian pressures and post-conflict reconstruction demands.

Its 50th anniversary celebration sadly came about the time when unpleasant news broke that Boko Haram terrorists had killed 17 people in Borno!

Imo faces political instability; security challenges linked to separatist violence and declining public confidence in governance.

Niger, despite hosting strategic national assets in energy and agriculture, suffers from banditry, underdevelopment and environmental challenges, including flooding and dam-related displacement.

In terms of endowments, Niger State, covering approximately 76,363 square kilometres, is the largest state in Nigeria by land area, and it is currently larger than each of the former Western and Eastern Regions at independence.

It accounts for about 8% of Nigeria’s total landmass, and it shares boundaries with seven states (Kaduna, Zamfara, Kebbi, Kogi, Kwara, Federal Capital Territory, and Nasarawa) and also has an international border with the Benin Republic.

The state hosts major water bodies, including River Niger, River Kaduna, and Kainji, Jebba and Shiroro dams, giving it strategic importance for agriculture and hydroelectric power.

Sadly, despite its size and natural endowments, population density remains relatively low, and large portions of the state are still rural and underdeveloped, with experts calling them (ungoverned spaces).

Till date, Ogun struggles with managing rapid industrialisation amid infrastructure strain, land disputes and environmental degradation, while Ondo continues to contend with declining agricultural productivity, weak diversification and policy inconsistency.

Ironically, at a time when the two neighbours should be rolling out the drums and trumpets, Ogun and Ondo states are currently locked in verbal war over the ownership of Eba Island, an oil-rich territory in the South-West, following President Bola Tinubu’s approval of drilling activities at an abandoned oil well on the island.

At the weekend, the Ogun State Government reaffirmed its territorial claim over Eba Island, located in Ogun Waterside Local Government Area.

It also called out Ondo State for claiming the right to the area, saying it was highly provocative.

In a statement on Sunday, Governor Dapo Abiodun’s Special Adviser on Information and Strategy, Kayode Akinmade, said the island falls squarely within Ogun State based on historical, legal, and administrative records.

However, Ondo State rejected Ogun’s claim, insisting that the island belongs to Atijere in Ilaje Local Government Area.

In a statement also on Sunday, Governor Lucky Aiyedatiwa’s Special Adviser on Communication and Strategy, Allen Sowore, accused Ogun of issuing misleading public statements and media briefings.

He said that while host states and communities are recognised, territorial claims must be established by historical records, documentary evidence, and statutory or judicial determination.

Across the seven states, common challenges persist, including overdependence on federal allocations, weak internally generated revenue, youth unemployment, insecurity, and governance and accountability deficits.

All said and without being immodest, if the late General Murtala were to look upon the seven states he midwifed on February 3, 1976, one suspects his heart would yearn less for their size or status, and more for their spirit. He did not create them as competitors locked in endless rivalry, but as partners in a shared national project, as units strong enough to govern themselves, but wise enough to lean on one another.

Murtala would likely have hoped to see these states bound by memory and purpose, recognising that their histories, peoples and economies are deeply intertwined. He would have been pained to see how political rivalries, ethnic suspicions and zero-sum thinking have often weakened collective capacity, even as insecurity, poverty, climate stress and infrastructure deficits cut across their borders without discrimination.

In his vision, cooperation would not be charity, but strategy. Each state has a comparative advantage, be it agriculture, human capital, commerce, natural resources or geographic position. Harnessed together, these strengths could form a single force greater than the sum of its parts in the form of shared markets, coordinated security, integrated transport corridors and joint investments in education and industry.

Leave a Reply